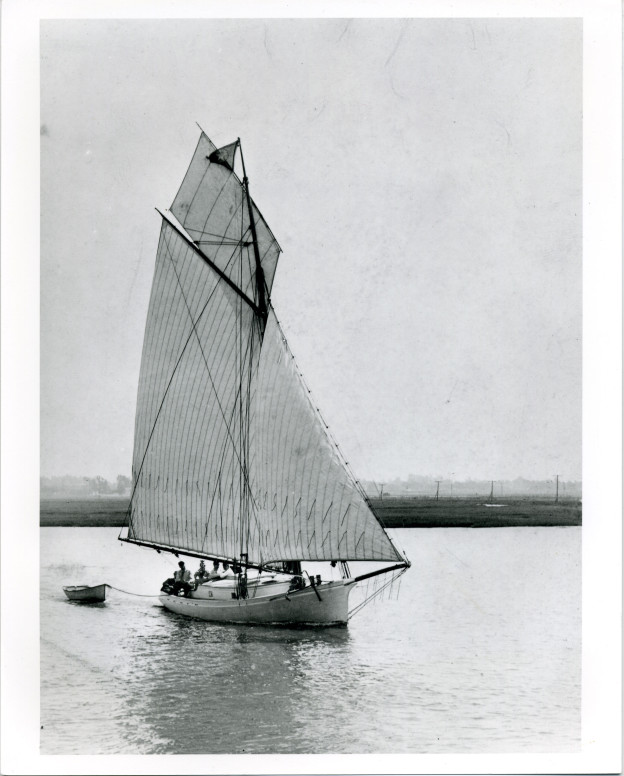

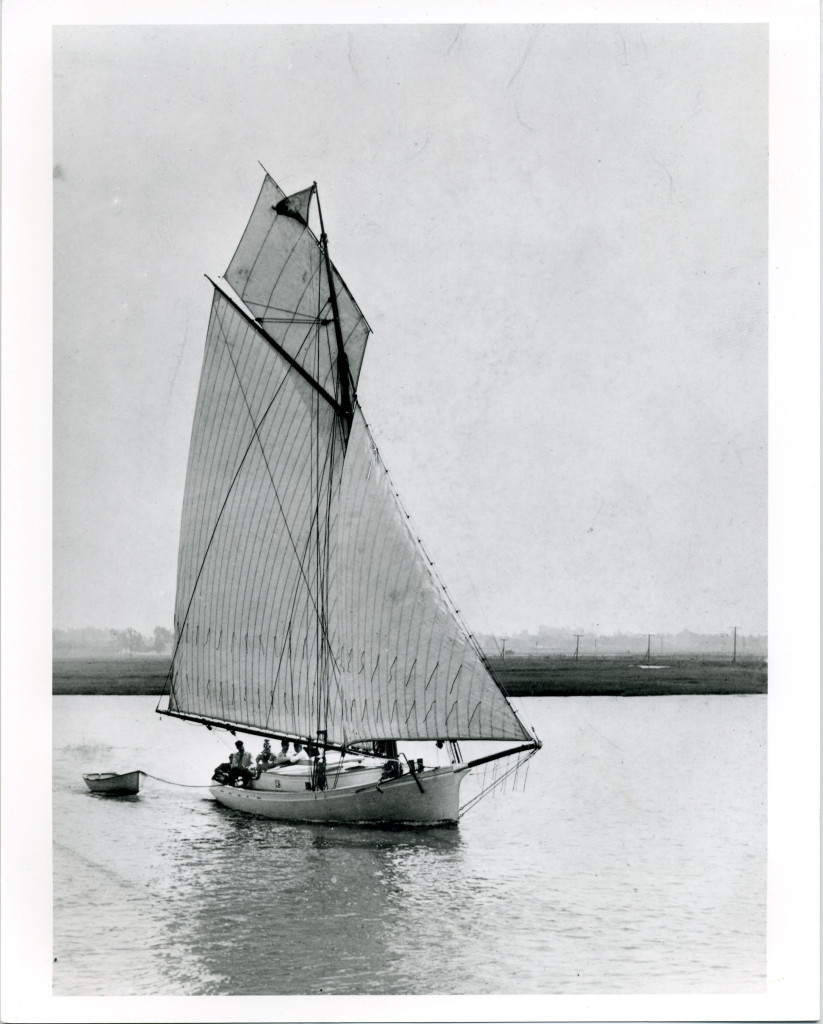

Freda

Freda is the oldest sailboat on the West Coast. She was built in 1885 in Belvedere for local racing and yachting. Freda was completely restored by the Arques School of Traditional Boatbuilding in Sausalito. The School cut sawn frames from curved Black Locust trees. The stem and sternpost are Pepperwood cut above Cazadero. Please visit the Freda Lines Project under Projects for more information about the process of creating a new set of Freda drawings.

A Few Words About the Importance of Freda

Bob Darr, February, 2016

The French were already in love with the American centerboard sloop when Freda was launched at Tiburon in 1885. The ‘clippers,’ as the French called their slightly modified versions of the fast New York sloop, had become the dominant racers at Argenteuil on the Seine River not far from Paris. Through a quirk of fate, they also found their place at the heart of French culture. This was because, by Freda’s time, an only recently maligned and marginalized group of painters known as the Impressionists had become wildly popular. The graceful American sloop, adapted for the conditions on the Seine, graced the tableaus of Monet, Renoir, and Manet––all of them sailors. The boats they sailed and captured on their canvases were just under thirty feet in length, and proportionately beamier and shallower than Freda. They were built with a bit of rocker along the keel to ease tacking and turning on the restricted waters of the Seine. These open boats were fitted with side decks and prominent coamings like their originals, the ‘sandbaggers’ of New York. The bright, sensitive portraits made by the Impressionists of the ‘clippers’ sailing and moored at Argenteuil continue to delight audiences everywhere, but few are aware of the American origins of the boats they depict.

Halfway around the world, on a beach joining Tiburon and Belvedere, Freda took shape at the apogee of the sloop’s development in America. She too was a descendent of the New York centerboard sloop––one adapted for windy San Francisco Bay. Freda was designed using the progressive-thirds formula, meaning that the hull’s beam was kept to about a third of the length, and the draft, board up, to about a third of the beam. Her hull is thirty-five feet long with twelve and a half feet of beam, and her original draft was nearly four feet. Like the New York sloops, Freda’s entry is sharp and very hollow at the load waterline. The San Francisco boats of the period often had round fantail sterns. A few, like Freda, were graced with shallow, curved, oval transoms raking back forty-five degrees or more off the vertical. Photographs of the period show dozens of similar boats on the West Coast in the last quarter of the 19th century. Like the French ‘clippers’ they were often raced. The San Francisco boats were longer, some over forty feet, and usually fitted with cabins and rudimentary accommodations below decks.

Freda is one of the few survivors of a handful of late 19th century American sloops built with wide, shallow, oval transoms. Freda is especially unusual in that her hull narrows in suddenly at the aft end with a tight curve that joins the oval outer edge of her broad transom. This type of stern was the most difficult to loft and build, and it represented the epitome of the American sloop’s aesthetic development. Tumble-home in the aft hull and curved, raked, transoms were fairly common sculptural features of the American schooners and yachts, and even some of the small fishing boats of the period. The tumble-home and delicate curves of these transoms had, over time, become increasingly suggestive of the human form. The sloops’ designers were heir to a long tradition, maritime and literary, of ascribing feminine beauty to sailing ships and yachts. In the April, 1970 issue of Rudder Magazine, author and sailor Ernest Gann passionately invoked this perspective in his description of Freda, with what might seem to the uninitiated like romantic hyperbole:

“I stood entranced for a long time, absorbing her poised loveliness as if she were mine alone to kidnap and sail away toward those dream harbors…..I caressed her overall grace with my eyes and saw at once that her master must also be in love. For there was not a single blemish or compromise anywhere. Her sheer was exactly right, being neither so marked as to suggest a wooden shoe nor so slight as to resemble a flat iron. Obviously what little water came upon her decks would soon slip back to the sea.”

As a boy sailing with my father in the early 1960s on the San Francisco pilot schooner Gracie S., I heard a lot of this kind of talk, inspired by the schooner’s lovely shape. Renamed Wanderer, Gracie S. had been built at Alameda in 1893. Freda, though much smaller, had similar lines which is probably why I was so drawn to her as a teenager.

During my career as a boatbuilder, I have built historical replicas with raked, curved transoms, and I’ve also designed a few. My experience makes me wonder about the historical account of Freda having been built by a local bartender by the name of Harry Cookson. It is indisputable that Cookson was the owner, and probable that he helped with the construction. However, Freda’s transom is so difficult to execute that I believe that a master of lofting and boatbuilding must have been involved with the project. Either that, or there is the possibility that history has overlooked Cookson’s training as a master boatbuilder.

While dismantling Freda’s rotted hull in preparation for rebuilding, we discovered that some of the original workmanship had been substandard while other work seemed to have been performed by a master builder. We can only imagine what the reasons for this might have been. I suspect that Cookson, the bartender, had some of the local boatbuilders and designers as clients. Bartenders often become the confidantes of their clients. Clients sometimes find themselves emotionally and even financially indebted to bartenders. I can imagine such a fellow directing Freda’s lofting and construction with amateurs helping out.

None of the materials used in Freda’s construction were particularly durable and it is nearly miraculous that Freda has survived the last one hundred and thirty years. We are lucky to have such a precious example of the maritime aesthetic of the 19th century. It is my hope that a broader understanding of Freda’s historical and cultural importance will ensure her maintenance and survival for many decades to come.

The restoration of the Freda has been performed by the apprentices of the Arques School of Traditional Boatbuilding over the last two decades, in several stages. On May 31st, 2014, Freda was re-launched at the Spaulding Center.